Weaving Personal Geographies with Tania Lara

Drawing from her Latin American roots and from counter-mapping methodologies, Tania Lara's latest work explores the oneiric dimensions of textile art.

I first met Tania the way normal people do: at a house party. After more than a couple of drinks, truth be told, I was not at my best, but despite my mess, she stayed as a friend.

With a soft voice and piercing eyes, Tania’s ability to make people feel at ease and attended, without any doubt, is one of her greatest talents as a human being; as an artist, she’s a jack of all trades.

Educated in painting and drawing, in her recent graduation show, autogéographies, at Galerie La Centrale (4296 Boul. St-Laurent; open until November 9), Tania explores the oneiric dimensions of textile art and challenges the conventional notions of how we perceive the geographies that conform us.

— Mauricio: I would like to start with the concept of auto-geography. How would you explain it?

— Tania: For me, auto-geography is a constant research process, which means you always search for things and search for others. It isn’t easy to give you an exact definition [of auto-geography] because that’s what it’s all about, facing research as something in motion, never-ending, and alive—how identities and territorialities are also considered often.

Auto-geography is also a personal and collective practice, as well as an invitation to explore and discover how collectives connect with their environment, geographies, and national histories because identities are always collective and collectives are always geographical.

— Mauricio: And what attracted you to this methodology?

— Tania: My practice has always leaned towards collective work. At first, I wanted to study anthropology and social work, then art therapy—always following the intention of working art in a transformative way and within processes that were already collective. At the same time, maps and their socio-historical value started to interest me a lot. That led me to counter-mapping which, different from conventional cartography, aims to represent space from the bottom up by focusing on situated, more personal experiences.

Then came the pandemic, which prompted me to enroll in an MA degree at UQAM; it was the perfect opportunity to sink my teeth into this research that had interested me for so long.

— Mauricio: When did you first realize it was possible to tell stories through textiles?

— Tania: Well, with my first collective cartography project in 2020 in Bogotá, with a group of around fifteen women. And, I somehow also relate it to a map’s historical weight, and how this becomes a myth and then a metanarrative that no one debates, and then that becomes a rule. Through textile art, I can also integrate what I’ve tried to emulate with my auto-geographical journey: to schematize the different places that constitute who I am because—as I’ve learned from kick-ass Latin American community feminisms that are very focused on territorial defence, and in a fight to radically change how we frame our worldviews—the first territories we inhabit are our bodies.

— Mauricio: What do you think a foreign perspective offers to the imaginary of a geography?

— Tania: I migrated from Mexico to Québec when I was seven, and I think that [migration] gave me the seed that resulted in my reflections around auto-geography: feeling like a foreigner here and then going to Mexico, only to feel even more foreign. That feeling and that experience really shaped my identity process—taking into account all the privileges that come with being Caucasian and coming from a lineage mainly European.

Édouard Glissant—who has been such a source of inspiration—differentiates between a rooted identity, one that wants to dominate and be the strongest—and that influenced Colonization a lot because it goes back to the myth of a master race—and a rhizomatic one, which strengthens with every connection it adopts.

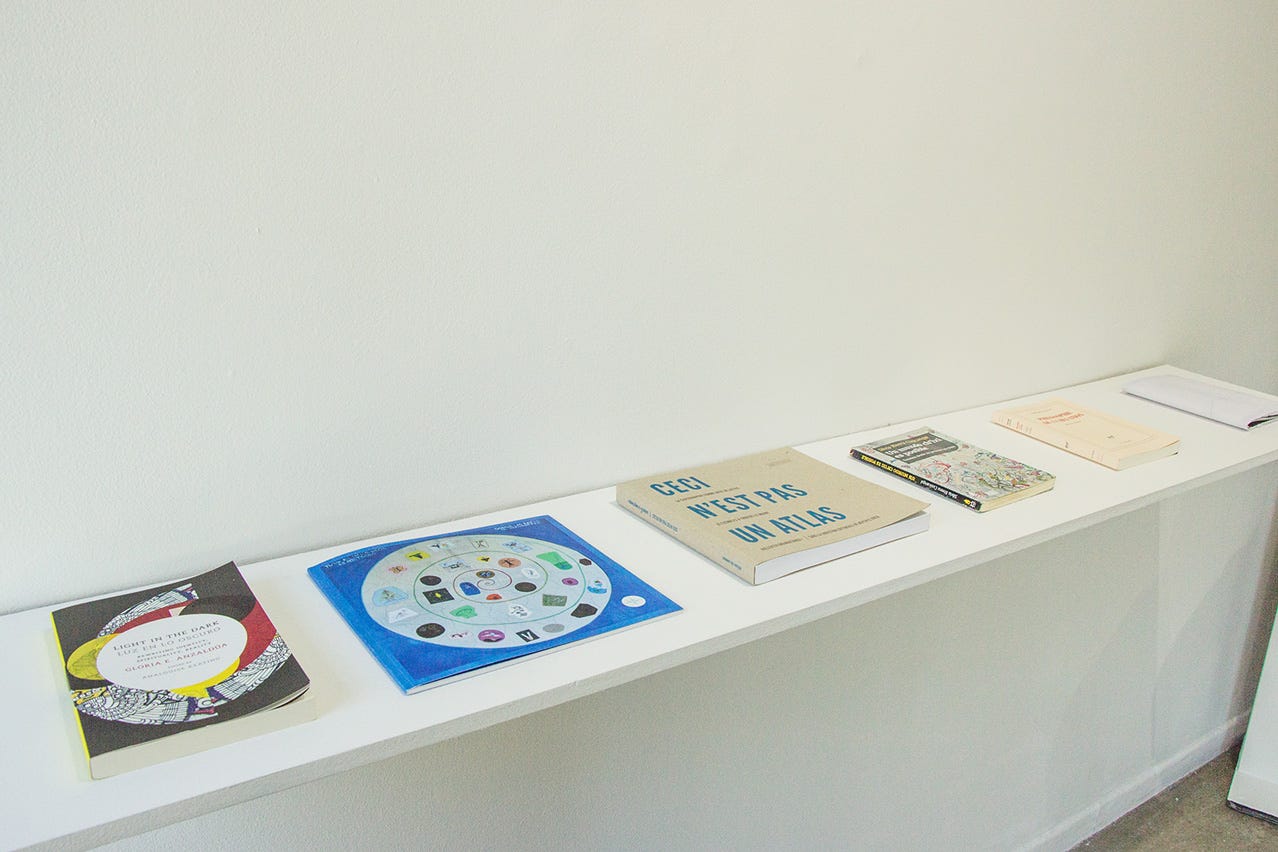

(At the front of the gallery, references from Tania’s research are presented to the public.)

— Mauricio: There’s a lot of semiotic work within the pieces in the exhibition. How was the process of synthesizing and symbolizing such personal experiences?

— Tania: I’ve always been a fan of symbolism. It wasn’t until recently that I started working with my dreams, and with all the things that appear in them: teeth, stairs—I’m always dreaming that I’m climbing up and down a set of stairs. So there’s a lot of my unconscious in the pieces. I also wanted to play with Capitalist imagery: the Chanel purse and the Adidas logo, for example, which have become almost like religious iconography.

— Mauricio: Considering that your formation started in painting, is there anything distinctive you've found in textile art?

— Tania: Textile work has always been a part of my family. I also started knitting and sewing with my mom, which has been super nice [in fact, one of the pieces in the exhibition was made during these mom-and-daughter sessions], and it has made me think a lot about my grandmother, a powerful woman. She wasn’t the typical grandma who floored you with hugs; her love language was giving us all the blankets she made with fabric scraps—she made so many, each grandchild had like, nine.

During this time, I also discovered Violeta Parra, an incredible singer-songwriter who also works with textiles; it was through her that I discovered arpilleras—a Chilean tradition that goes back to the years of the dictatorship, and when women sewed and illustrated blankets with sometimes-gruesome scenes from the conflict years and, since they were just ‘blankets,’ the Government couldn’t claim censorship. All of this together made me fall in love with textile art; the fact that it has survived as a domestic practice, denouncing injustice while gossiping in the kitchen.

(A 1986 arpillera aptly titled, The Coup; 5 x 19 ¾ inches) [source: Museum of Latin American Art]

(A snapshot from Río Arriba, a collective exhibition in which Tania collaborated with Javier Bernal and Karina Arbelaez, that included a textile piece meant to be finished by guests.)

— Mauricio: What place does the concept of time occupy in your practice?

— Tania: I’ve always been drawn to space. But to challenge the binary, I try to perceive space and time as unseparated entities; I try to approach them closer so they can breathe life into the other. It was one of my main goals to integrate video projections into the textile pieces because they bring a ‘temporal aspect’ with their movement looping endlessly—Karina Arbelaez helped me as technical director.

There’s a geographer who inspires me so much, Doreen Massey. She really pushed for this notion of critical geography, which eventually led to feminist geography. One of her main purposes was to bring space alive and to re-centralize space itself. She spoke a lot about the geographical dimension binding us all as a planetary society because it’s the one dimension that confronts us to encounter simultaneity.

— Mauricio: Now, to wrap up the interview, what’s in your interest these days?

— Tania: With the risk of sounding like an old lady, what I want right now is reconnecting more with my body, and watering my flowers—symbolically and figuratively.

Further Readings

Anzaldua, Gloria. Luz en lo Oscuro/Light in the Dark; Duke University Press, 2015.

Edited by Kollektiv Orangotango+. This Is Not An Atlas.

Montanaro, Mara. Théories Féministes Voyageuses; Rue Dorion; 2023.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. A Ch’ixi World is Possible; Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.